I’m a bit ashamed to say that history was probably my weakest subject in school. Even so, learning about the French Revolution of the 1780s and 1790s left a relatively strong impression on me. This is greatly oversimplified, but for the sake of this review, let’s just say it was a period of great political upheaval in which the monarchy and the feudal system were ousted, and it entailed a lot of chaos and bloodshed. I think this is important to understand going into this game because though you play a judge in We. The Revolution, this is not a courtroom drama or a criminal investigations kind of game. You won’t be applying legal doctrines or examining much evidence. It’s primarily a historical simulation, and from what I understand of that time period, probably accurate in its brutality and the oppressive weight of its pervasive unfairness.

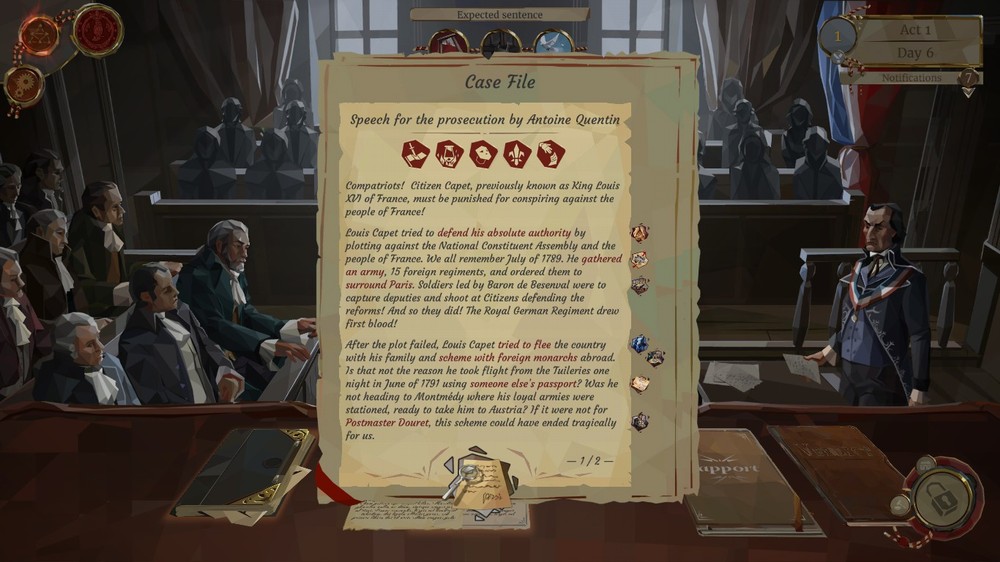

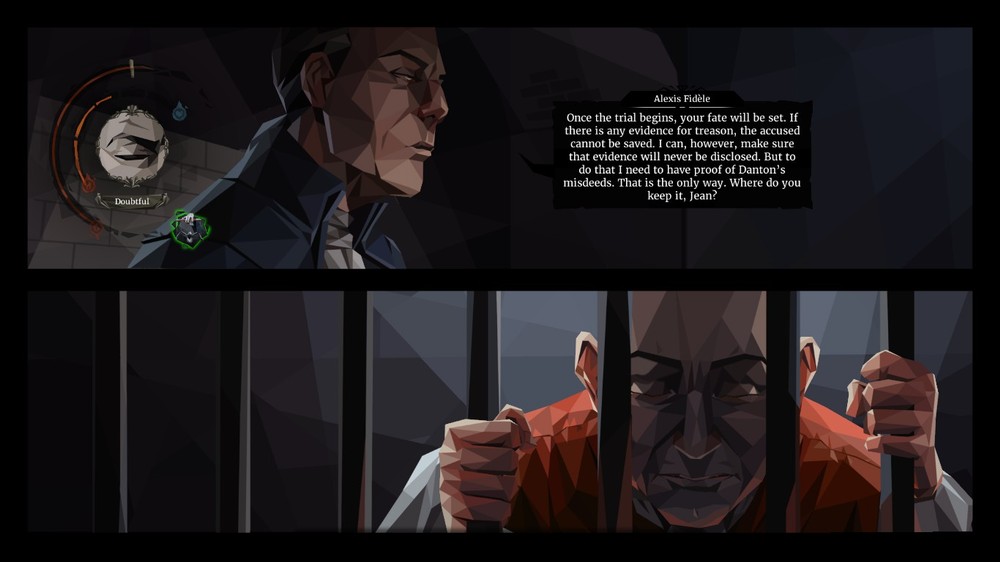

You play Judge Alexis Fidelis, apparently a known gambler and drunk, who also happens to be a hapless lowly cog in an unforgiving political machine that you soon discover you have little control over. Sure, you preside over a courtroom where you hear cases and pronounce life-or-death judgments day in and day out, even personally handling the executions by guillotine when they come up, but it soon becomes painfully obvious that justice is a laughable ideal in this system. You’re given some minimal documents that explain each situation, and from these documents, you’re expected to connect various statements to categories such as witnesses, evidence, and accusations. When you get the connections right, you’re rewarded with an unlocked question that you can ask the accused.

While some category connections are fairly straightforward (the documents, for instance, will typically tell you clearly what the accused is charged with, and what items constitute evidence is usually obvious enough), there is often seemingly no rhyme or reason to which category a statement connects to, so there is a significant amount of guesswork involved. That said, the questions are almost entirely leading questions designed to herd the jury toward your preferred opinion (acquittal, jail, or immediate execution), and the final outcome that you find affects your standing with various factions (such as the people, the revolutionaries, and the aristocracy), as well as with various members of your family.

While some category connections are fairly straightforward (the documents, for instance, will typically tell you clearly what the accused is charged with, and what items constitute evidence is usually obvious enough), there is often seemingly no rhyme or reason to which category a statement connects to, so there is a significant amount of guesswork involved. That said, the questions are almost entirely leading questions designed to herd the jury toward your preferred opinion (acquittal, jail, or immediate execution), and the final outcome that you find affects your standing with various factions (such as the people, the revolutionaries, and the aristocracy), as well as with various members of your family.

You’ve got to listen to the jury, and your report – a kind of multiple-choice quiz on the facts of each case – needs to be accurate, or your reputation takes a hit. As the game progresses, it becomes more and more evident that there’s simply no use in trying to find even a shred of justice in passing these judgments; the only thing that matters in the end is that you keep the various factions happy so that Alexis doesn’t get himself guillotined. The more you play, the clearer this message becomes.

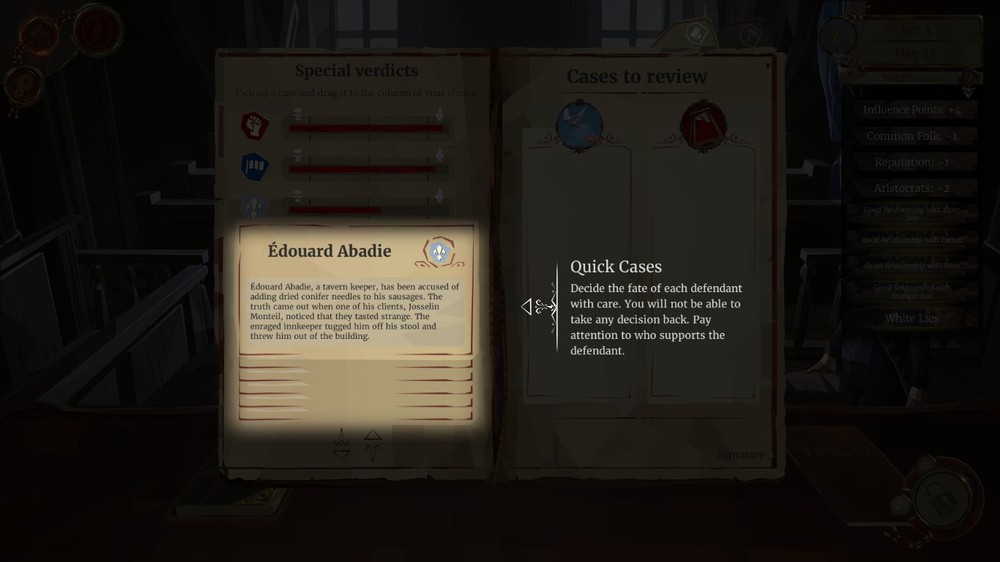

Eventually, you’ll need to also worry about the impatient crowd rioting if you ask the accused too many questions, further pressuring you to wrap up cases quickly (and asking only the questions that guide the jury toward your desired reputation outcome) instead of with any amount of actual fairness. Later on, you’ll even have an additional docket of quick cases you’ll have to make snap judgments on after only reading a short summary of the facts and weighing how the decisions affect your reputation with each faction.

Eventually, you’ll need to also worry about the impatient crowd rioting if you ask the accused too many questions, further pressuring you to wrap up cases quickly (and asking only the questions that guide the jury toward your desired reputation outcome) instead of with any amount of actual fairness. Later on, you’ll even have an additional docket of quick cases you’ll have to make snap judgments on after only reading a short summary of the facts and weighing how the decisions affect your reputation with each faction.

Then, at the end of each day, Alexis goes home to his family – his father, his wife, and his two sons – and must choose how to spend the evening. This, too, is a faction-balancing activity, as family relationships also affect your standing: your father has ties with the people, your elder son has ties with the Revolution, your relationship with your wife affects your overall reputation, and your relationship with your younger son affects your relationships with the other family members. For example, choosing to make your elder son, whose passion is music, study law will decrease your relationship with him (and, therefore, the revolutionaries) and, to a lesser extent, your wife (and damaging your public image) but increase your relationship with your father (and, therefore, the people).

Meanwhile, choosing to take a stroll will make everyone happy except for your elderly father; and working on the next day’s cases or facilitating the building of a statue that the government wants you to finish on a tight deadline irritates all your family members. It’s always choosing between a rock and a hard place in this game, which I imagine is the point. And, if that’s not unhappy enough, there are days that something out of your control happens (say, an assassination attempt), that prevents Alexis from spending any time with his family, which causes relationships to plummet all around. You might say this is unfair, and it is, but it’s the French Revolution, and unfairness and suffering are pretty much your meat and potatoes.

Meanwhile, choosing to take a stroll will make everyone happy except for your elderly father; and working on the next day’s cases or facilitating the building of a statue that the government wants you to finish on a tight deadline irritates all your family members. It’s always choosing between a rock and a hard place in this game, which I imagine is the point. And, if that’s not unhappy enough, there are days that something out of your control happens (say, an assassination attempt), that prevents Alexis from spending any time with his family, which causes relationships to plummet all around. You might say this is unfair, and it is, but it’s the French Revolution, and unfairness and suffering are pretty much your meat and potatoes.

At the end of each day, you’re also given the opportunity to move your agents around a map of Paris, as gaining and maintaining territory in the city through your agents will allow you to improve your standing with various factions, as well as increase your influence, which in turn gives you Influence Points to use toward actions such as gaining insight on political opponents or someone you’re trying to court favor with. This aspect of the game was the most frustrating to me, as your mysterious political nemesis always seems to have more agents than you do (which allows them to easily incapacitate your agents or take over areas of the map more quickly than you can protect them), and there are additional third parties that are hostile to both you and your opponent.

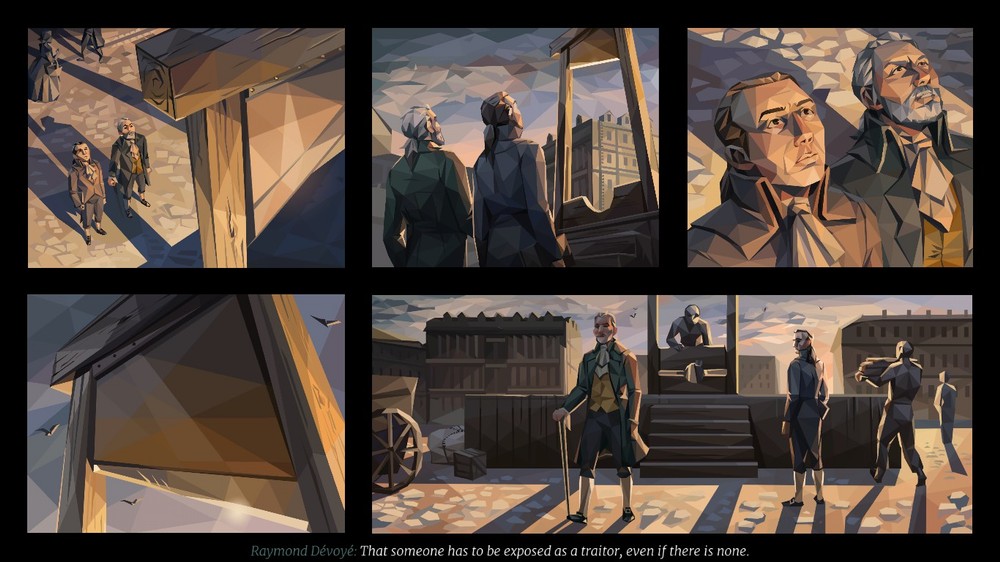

There are also political intrigues involving rooting out your political rival that occur between court days. The intrigue events are some of the more interesting portions of the game, as they propel along Alexis’s personal storyline and include some of the more gripping scenes in the game. These intrigues seem to frequently involve persuasion, which requires you to either discover (by spending earned Influence Points based on how much territory Alexis controls) or guess at your audience’s attitude toward a topic and then to respond with the correct tack when approaching a subject. Because gaining territory is so dicey with the unbalanced numbers of agents on the map, though, I found that this process also generally involved a lot of guesswork, as I never had much Influence to spend.

There are also political intrigues involving rooting out your political rival that occur between court days. The intrigue events are some of the more interesting portions of the game, as they propel along Alexis’s personal storyline and include some of the more gripping scenes in the game. These intrigues seem to frequently involve persuasion, which requires you to either discover (by spending earned Influence Points based on how much territory Alexis controls) or guess at your audience’s attitude toward a topic and then to respond with the correct tack when approaching a subject. Because gaining territory is so dicey with the unbalanced numbers of agents on the map, though, I found that this process also generally involved a lot of guesswork, as I never had much Influence to spend.

We. The Revolution effectively creates an atmosphere of chaos and helplessness, which I think is purposeful, given the bloody period of history it simulates. It’s certainly a unique and potentially distressing game experience that requires a stomach for (simulated) injustice and one that, somewhat unexpectedly, inspires some sympathy toward characters like Alexis Fidelis, who, given the inescapable pressures of the political climate, inadvertently become villains reminiscent of The Count of Monte Cristo’s Villefort. It’s a thought-provoking—though maybe not the most relaxing, fair, or even necessarily fun—game. The highly stylized, angular, and largely monochromatic art style (reminiscent of vintage propaganda posters) and the morose soundtrack fully complement the harsh and oppressive atmosphere of Alexis’s world.

We. The Revolution goes for $19.99 on Steam, which I think is a reasonable price for the impactful and educational experience (particularly if, like me, you end up brushing up on the French Revolution after playing) that this game offers. It’s not kid-friendly by a long shot but could maybe be an interesting simulation supplement to history class for a more mature pre-teen or teen, probably with parental guidance.