The Evolution of Adventure

Originally Published on November 13, 2003

The Evolution of Adventure

As the stream of time inexorably marches forward, and we enter the dawn of a new year, the gaming industry continues its relentless expansion – like the borders of our universe, abandoning the worlds of yesterday and cradling the embryonic territories of tomorrow. Anyone who has read basically any gaming publication in the past decade can name the genres that dominate the industry today – MMO, FPS, RPG, RTS, Simulation, Platform, Sports, Action, Fighting, Racing, Shooter – but among them is a genre that is often overlooked, though it is one that evokes a certain sense of nostalgia in gamers who remember a time before portly Italian plumbers and ill-tempered space marines. Its roots can be traced back to the immemorial age of Atari and Intellivision, and it has certainly come a long way since then yet has not abandoned the fundamental aspects that brought it into being. Follow me then, into the history of a world where progression sometimes required the player to input entire sentences, and almost always required the player to provide something that modern games seek to eradicate – imagination.

> Genesis

To mark the beginning of the Adventure genre, we must travel back to the years when the frontiers of the Internet were still wild and mostly unsettled, when what is known as “classic” rock today was contemporary, when the term platform was used to describe a style of footwear as opposed to a style of game. Though the genre would see its climax, and ultimate decline, during the Generation of Swine (to borrow a term from Hunter S. Thompson), its humble origin preceded the 80’s by a few years. Aptly enough, the first recognized Adventure game was titled…wait for it…Adventure (originally Advent).

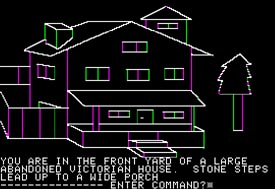

Created by a spelunker and programmer by the name of William Crowther, Adventure defied the conventions of its analog cousins by forcing the player to make careful decisions concerning their interaction with the fictional environment. Not only did they have to evaluate more than where to jump next, or what to shoot at, but they also had only a blurb of text to guide them. You heard right – text – the same form of information that this article is composed of. Absent were the blocky renditions of perilous jungles and intergalactic battles, replaced by a few lines of text that told you where you were, what you could see, and possibly where you could go next.

After Mr. Crowther distributed his game through ARPAnet, the form caught on. Students and enthusiasts modified Adventure (as was the custom back then) to create their own versions, and some sought to build their own Adventure games from the ground up. Thus, the genre staple of Zork was born, and the boundaries that guided the birth of countless Zork descendants were clearly identified.

Surprisingly, in this modern age of pixel shading and anti-aliasing, the text adventure format persists to this day, alive and well.

> What’s Your Interface?

Since the principal concern of this article is the evolution of the Adventure genre, it is necessary then to chart the growth and permutations of the most important aspect of any game – its interface.

As mentioned above, Adventure and Zork provided players with an all-text interface to navigate themselves through the game. Though this sort of interface endured a number of alterations and tweaks, in its basic form, the game would describe a location, and the player would respond via a prompt that allowed the input of basic commands: go North, get sword, use key, etc. Zork soon spread through the incipient industry like wildfire and elevated the genre to a level of legitimacy and popularity that would continue to wax for the next ten years, beneath the yoke of this simple interface.

The inception of Sierra Online in 1980 brought the inclusion of graphics to the genre, crude though they may have been, with the release of Mystery House. Their next release added color to the equation, and the game that would come next irrevocably changed the genre, bringing Sierra unprecedented commercial success. That game was King’s Quest, and unlike its all-text predecessors, it brought immersive (at the time, mind you) pseudo-3D graphics and an entirely new interface to the table. Coined Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI), the interface consisted of a domineering window that displayed the player’s in-game ego and his/her environments, with a prompt at the bottom for text commands and a series of hidden drop-down menus at the top for access to inventory and game configuration options. Like previous Adventure titles, gamers still had to craft awkward commands to perform certain actions, but now the results were displayed via animation before their very eyes. The player’s ego was controlled via the arrow keys, a mechanic which became responsible for a number of frustrating arcade style sequences and impossible feats of navigation.

The inception of Sierra Online in 1980 brought the inclusion of graphics to the genre, crude though they may have been, with the release of Mystery House. Their next release added color to the equation, and the game that would come next irrevocably changed the genre, bringing Sierra unprecedented commercial success. That game was King’s Quest, and unlike its all-text predecessors, it brought immersive (at the time, mind you) pseudo-3D graphics and an entirely new interface to the table. Coined Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI), the interface consisted of a domineering window that displayed the player’s in-game ego and his/her environments, with a prompt at the bottom for text commands and a series of hidden drop-down menus at the top for access to inventory and game configuration options. Like previous Adventure titles, gamers still had to craft awkward commands to perform certain actions, but now the results were displayed via animation before their very eyes. The player’s ego was controlled via the arrow keys, a mechanic which became responsible for a number of frustrating arcade style sequences and impossible feats of navigation.

Despite the complaints of many enthusiasts that the fancy graphics detracted from the literary standards of the genre, the AGI interface served as the foundation for the plethora of Sierra releases to follow King’s Quest, and enabled Sierra to enjoy a resounding dominance over the market. It is here that we see the creation of some of the most successful Adventure games and series ever – Police Quest, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry, Mixed-Up Mother Goose, and so on. Gamers worldwide were introduced to the sometimes wacky, sometimes grim exploits of King Graham, Roger Wilco, Larry Laffer and countless others.

Despite the complaints of many enthusiasts that the fancy graphics detracted from the literary standards of the genre, the AGI interface served as the foundation for the plethora of Sierra releases to follow King’s Quest, and enabled Sierra to enjoy a resounding dominance over the market. It is here that we see the creation of some of the most successful Adventure games and series ever – Police Quest, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry, Mixed-Up Mother Goose, and so on. Gamers worldwide were introduced to the sometimes wacky, sometimes grim exploits of King Graham, Roger Wilco, Larry Laffer and countless others.

Sierra’s lofty position would not be challenged until the latter half of the 80’s, when LucasArts released their quintessential Adventure title, Maniac Mansion. LucasArts took a bold step and forged their own interface in lieu of the now standard AGI. SCUMM, or Script Creation Utility for Manic Mansion, eschewed the reliance on text input and instead allowed the player to choose from a preconceived list of verbs, nested in a window at the bottom of the screen, to interact with certain objects and characters. And, instead of guiding the characters through the environments with the arrow keys, Maniac Mansion enabled players to use a strange and new device – the mouse.

SCUMM relieved much of the frustration that AGI games were prone to cause, and forced Sierra to rethink their practices, which eventually led to the formation of new interfaces for Sierra titles. SCUMM also brought us the classic example of an Adventure game – The Secret of Monkey Island. LucasArts would later abandon SCUMM in favor of a new trend in Adventure game format, the iconic interface. This interface was employed in another LucasArts classic, Sam and Max Hit the Road.

SCUMM relieved much of the frustration that AGI games were prone to cause, and forced Sierra to rethink their practices, which eventually led to the formation of new interfaces for Sierra titles. SCUMM also brought us the classic example of an Adventure game – The Secret of Monkey Island. LucasArts would later abandon SCUMM in favor of a new trend in Adventure game format, the iconic interface. This interface was employed in another LucasArts classic, Sam and Max Hit the Road.

Now, instead of typing commands or choosing from a textual list, players choose from a group of icons that represented basic actions and clicked the appropriate spot in the game to perform an action. The iconic style, like AGI and SCUMM before it, reigned supreme over the next few years. By this time, text commands were considered archaic, and Reagan was no longer in office.

> The Dark Ages

With the onset of console gaming steadily conquering the living rooms and televisions of horrified parents everywhere, interest in Adventure games began to decline. With the success of the NES and SNES, Nintendo cut a swathe through the gaming industry like a horde of barbarian raiders. Though the 90’s would be witness to the release of some of the greatest Adventure titles ever – Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, Grim Fandango, King’s Quest VI, Full Throttle, Curse of Monkey Island, etc. – it would also prove to be a very trying time for the genre as a whole.

With the onset of console gaming steadily conquering the living rooms and televisions of horrified parents everywhere, interest in Adventure games began to decline. With the success of the NES and SNES, Nintendo cut a swathe through the gaming industry like a horde of barbarian raiders. Though the 90’s would be witness to the release of some of the greatest Adventure titles ever – Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, Grim Fandango, King’s Quest VI, Full Throttle, Curse of Monkey Island, etc. – it would also prove to be a very trying time for the genre as a whole.

Blame is often laid on the revered and perhaps overpopulated beast known as Myst. The first-person perspective and lack of a windowed interface annoyed a great many but enthralled a great many more. The focus now shifted from narrative and plot to puzzle solving, and though it was obviously exactly what millions of people were looking for, many complained that the experience was too cosmetic.

Games like 7th Guest (though it terrified the hell out of me) and Myst were little more than a sequence of puzzles, but the cinematic graphics were a vast improvement over those of their ancestors, and their sales figures easily rivaled those of other uber-successful titles. Many Adventure games were hard pressed to compete with the likes of these newcomers, and new genres like First Person Shooter and Survival Horror were being refined into the monoliths that they are today.

Myst clones began to populate the bargain bins of software stores, and many gamers lost their patience for the Adventure genre, opting for games with more violence and fast-paced action instead. Even Sierra and Lucasarts themselves began publishing fewer Adventure titles, following the trade winds of the industry and shifting more toward action.

The genre has never really recovered from the shift in interest, and today remains mostly the domain of hardcore, devoted fans. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing but does mean that the halcyon days of high-profile Adventure releases are all but dead.

> Press ENTER To Quit

The number of upcoming Adventure releases I’m excited about can be counted with ten fingers, but in truth, the genre is slowly recovering from the grievous blow it suffered when gamers were seduced by the demonic charms of games like Doom. I too abandoned the genre to pursue hellish beasts and RPGs from exotic lands. But I likely wouldn’t be a gamer today if it weren’t for the talents of people like Jan Jensen, Roberta Williams, Ron Gilbert, and the Two Guys from Andromeda. I owe much to the genre, and still have pangs of nostalgia that force me to fire up the old DOS emulator and relive the adventures of my youth.

With games like Black Mirror, Dark Fall 2, and Syberia 2 on the horizon, perhaps we will see a triumphant revival of the Adventure genre. Regardless, I will continue to hunt through wonderfully rendered environments and inane inventory items until I find the combination that will bring me to the next puzzle, as long as I have the mental capacity to do so. That could be anywhere from five to fifty years.

David Caviness